The digital advertising ecosystem spends a fair amount of time and energy discussing and addressing the issue of “brand safety; several studies have been conducted and are summarized in this eMarketer article.

The concept of brand safety is fairly simple: brands don’t want to have their ads shown in places where consumers might have a lesser opinion of the brand as a result of seeing the brand’s ad in that context.

Magna Global attempted to quantify that negative impact in a recent study whose findings state that “ads appearing near negative content result in a 2.8x reduction in consumers’ intent to associate with these brands.”

Of course that’s what happens if you ask consumers about it. And the wording of a question can create very interesting results. (I didn’t see the questions, but imagine being a consumer asked: “do you feel that a brand is exploiting the shock value of an article by advertising on a story about a school shooting?” Does that question really reflect how a consumer feels about a brand after reading two stories side-by-side, one about a kitten rescued by a firefighter and the other about a school shooting? What if you asked the reader the next day?)

Well, that’s gonna have to be a different study 😉

When you ask marketers to define the concept of “brand safety,” many can’t really put their finger on a precise definition. Generally, however, they tend to classify “brand unsafe inventory” in the following three categories:

- generally unsafe content (e.g., a picture adjacent to a story recounting a genocidal attack)

- brand-averse content (e.g., a suitcase ad next to an article about a body being found in a suitcase)

- vertical-averse content (e.g., candy bar advertising paired up with a video about obesity, diabetes, and/or increased mortality)

The easiest form of brand safety to identify is #1.

YouTube continues to struggle with brand safely both as a result of some content creators having dubious reputations regarding racism or vulgarity, as well as sporadic posts on hot or sensitive topics from otherwise well-respected content providers. Publishers and Advertisers jointly agree that if a page or ad placement is considered to be non-safe for the advertiser, the advertiser doesn’t have to pay for the placement (even if they were the high bidder in the ad auction.)

Clouds Got in My Way

It’s been fascinating to watch the continued industry dialog around brand safety, as well as to occasionally take screenshots when I see evidence that an ad was stopped and replaced.

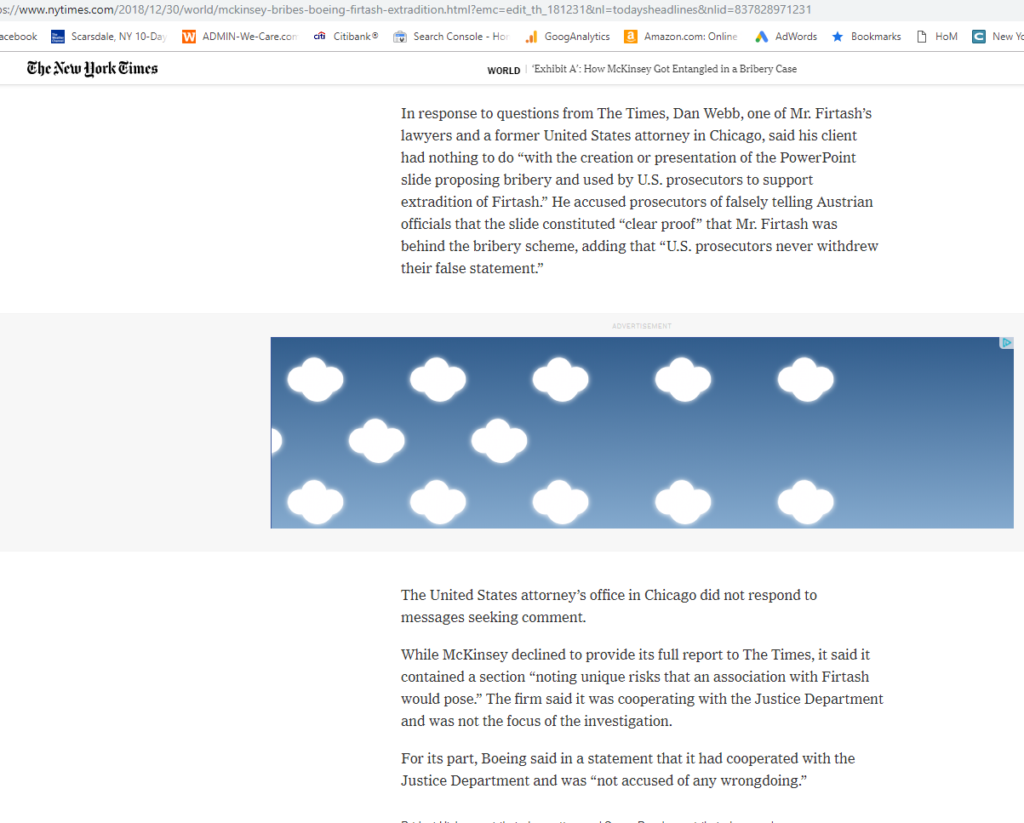

One of the major players in the brand safety category is Double Verify. When they find a brand-unsafe environment with respect to a specific advertiser and specific content, you are likely to see clouds replace the ad.

See examples below. Now you’ll watch out for the “brand safety” clouds as you surf around (turn your ad-blocker off). 😉

As you can see in the first file HTML inspection, Double Verify was protecting the advertiser.

Crossing the MOAT:

The clouds we see from Double Verify aren’t the only proof that a brand-unsafe trigger has occurred.

MOAT also has it’s own replacement for a banner slot.

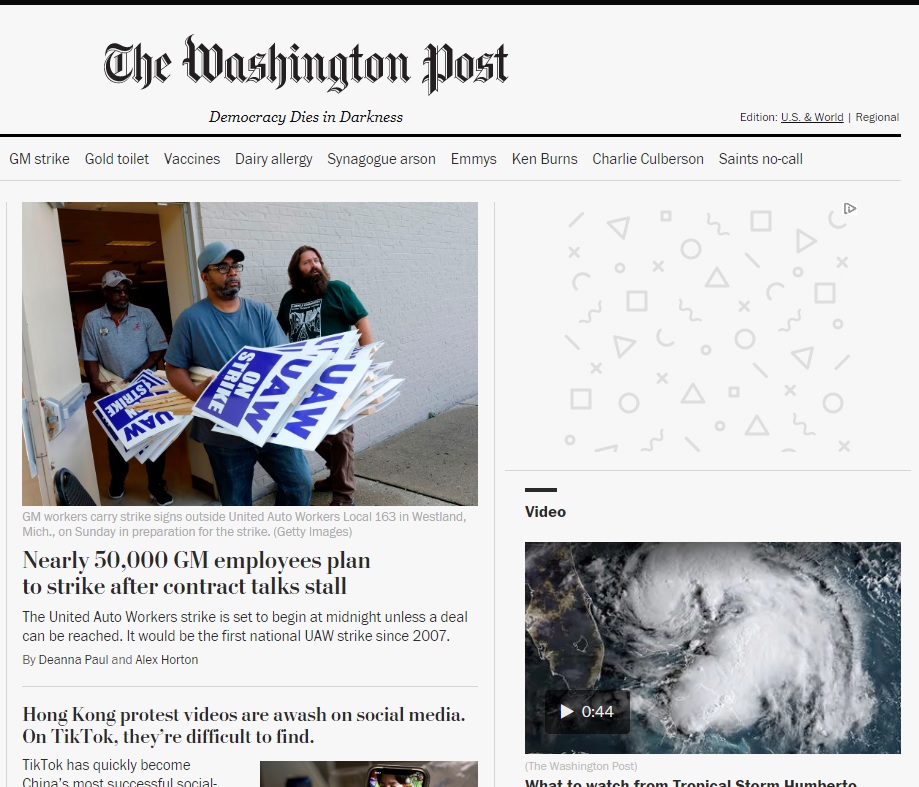

Sometimes even the super-valuable hompepage inventory will be blocked as in this Washington Post example.